No products in the cart.

Welcome to the newest revelation in our journey through the Shadows of Extinction universe. As 2024 dawns, we find ourselves amid an unfolding saga that has reshaped the African continent and altered the course of history – the eruption of Mount Cameroon, a cataclysm that redefined not only the physical landscape but also the socio-political fabric of our universe.

Alongside other significant events like the relocation of the United Nations Headquarters and the emergence of new geo-political entities, we follow the pivotal moments that have carved the destiny of Dr. Jenebah Tamba.

…and so the story continues

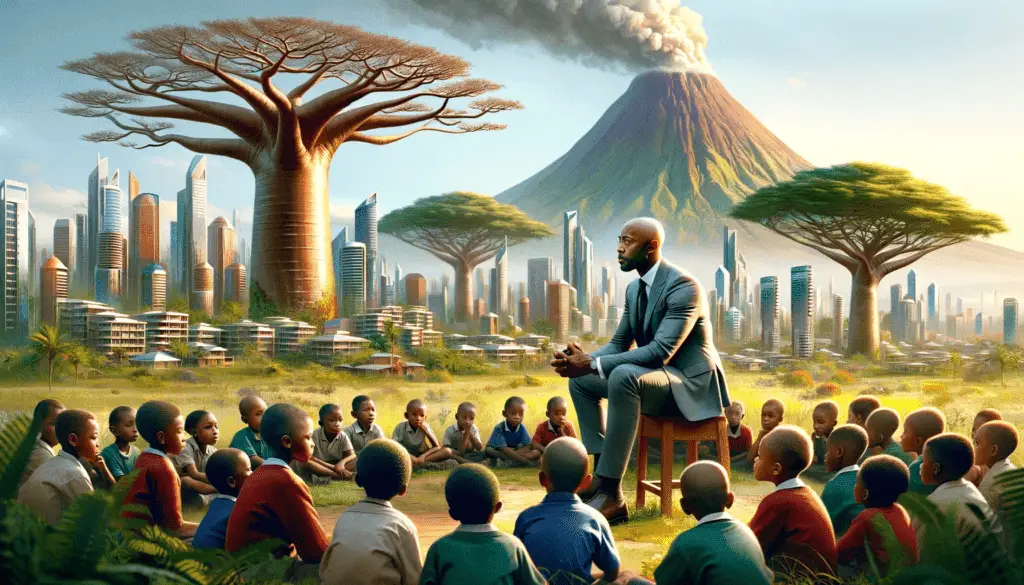

Imagine an ancient baobab tree, its expansive canopy sheltering a circle of young, inquisitive minds. Mr. Ekene, a storyteller par excellence, prepares to unveil a chapter of their history marred by turmoil yet rich in transformation.

Today, the breeze was unusually whimsical, and the ancient baobab stood proud; its leaves fluttered ever so slightly in the wind, welcoming the group of children, their faces alert with curiosity and excitement. They had waited patiently all week for this moment, looking forward to the last class of the day, Mr. Ekene’s Friday afternoon outdoor history class.

Known for his captivating storytelling, Mr. Ekene prepared to unravel the next chapter in their exploration of history. His gaze reflected the gravity of the tale ahead as he addressed his young audience with a voice that seemed to echo the very tremors of the earth.

“Today, we venture beyond the eruption into the heart of its aftermath,” he began, his words painting a vivid tapestry of the unseen and untold. “When Mount Cameroon awoke in fury, it did more than scar the land; it set in motion a cascade of events, each more impactful than the last. The eruption was but the first ripple in a vast ocean of change.”

The children, their imaginations kindled by his words, leaned in closer, drawn irresistibly into the narrative’s embrace. Their hearts, in that moment, seemed to beat in harmony with the pulsating rhythm of a story that promised to captivate.

“You see,” Mr. Ekene continued gently, “when Mount Cameroon erupted, it wasn’t just the ash and lava that changed the landscape. The massive plume of ash that shot into the sky spread far and wide; it covered many nations, altered our climate, and caused this beautiful continent to fall into chaos.”

A young girl, Abeni, raised her hand. “Sir, how can a mountain do all that?” she asked.

Praising the child for her insightful question, Mr. Ekene explained in his usual calming tone. “Looking at the mountain now, it is hard to imagine such a gentle giant causing so much pain and destruction, but when the mountain erupted that frightful day, it unleashed a vast cloud of ash and smog, veiling the skies over our lands in an unnatural twilight. This curtain of ash hung like a fog and dimmed the sun’s warmth, which caused the temperatures to drop and a chill to seep into the layers of the earth and starve the plants of their much-needed sunlight.”

The children nodded, beginning to grasp the enormity of the unfolding event.

“As the climate rapidly changed,” Mr. Ekene narrated, his voice resonating with the gravity of his words, “rainfall became scarce. Our once fertile land, lush and giving, found itself thirsty. People had to go long distances as wells dried up. Plants struggled and died without sunlight and water.”

“But…, children, this was only the beginning of a crisis that lasted many years. The water crisis was not just about the lack of rain but also about how we, as a people, were unprepared for such drastic changes.”

He paused, pacing thoughtfully under the tree. When he continued, his voice was serious but kind.

“Water became as precious as gold. Imagine, for a moment, queues of weary people stretching like endless rivers, having walked for miles, lined up for hours at a reservoir, hoping to fill their buckets. People got angry over the simplest things, and the once-bustling streets turned into arenas of frustration and protest.”

A young boy, Kwame, couldn’t help but ask, “Did people really fight over water, Mr. Ekene?” His eyes wide with a mix of concern and curiosity,

“Yes, Kwame, sadly, people did.” His expression mirrored the gravity of the situation. “In the countryside, it was even worse. Relief trucks were highjacked, limiting water supplies to farmers and villages. Fields of cocoa beans, groundnuts, maize, cassava, and yams all withered and died. The cattle could find no water to drink, and fresh goat and cow milk were a rarity, as the animals were too dehydrated to produce sufficient.”

“Governments across our lands were caught unprepared,” Mr. Ekene explained. “Their responses to the crisis were slow, plagued by old bureaucracies and limited resources. The people’s trust in their leaders waned as promises fell short and actions came too late.”

“The crisis that ensued was not merely a saga of nature’s wrath,” Mr. Ekene intoned with a gravitas that filled the air, “but equally a chronicle of our own human failings.” His voice, somber and resonant, seemed to echo the dual tragedy of the tale.

A hand shot up from among the students, a bright-eyed girl named Abba. “Sir, why couldn’t the governments do more? Weren’t they supposed to help?”

Mr. Ekene nodded, acknowledging the question. “The Governments did try, and so did the African Union, but they were overwhelmed by the scale of the crisis. And sometimes, their political interests and disagreements hindered their ability to respond effectively.”

“The water shortage led to more than just thirst. Starvation and disease followed; tempers flared, and soon protests erupted around the continent.”

“In some places, these protests turned violent. The people were desperate, and they felt their voices were not being heard,” Mr. Ekene added, his face reflecting the gravity of the situation.

With a deep sigh, he stopped talking for a moment. This gave the children time to absorb the information and imagine the scenes of desperation and frustration that led to the anger and then rage that ensued.

“Help did come from beyond our borders,” Mr. Ekene finally continued, shifting to a more hopeful part of the story. “Countries and planetary governments around the world sent aid. But even this help was not simple. Delivering aid to so many, in such challenging conditions, was a monumental task.”

“Did the aid make things better?” asked Amadou, a curious boy at the back.

“It helped Amadou, but we need to understand how big the disaster was,” he said, spreading his arms wide and flaring them in the air, causing the children to giggle. “The help we got was good, but it wasn’t enough for all our problems. It was like trying to cover a large sore with a tiny band-aid,” Mr. Ekene explained.

“As our ancestors faced those daunting challenges, little did they know that these were just the precursors to a larger storm brewing on the horizon,” Mr. Ekene intoned, drawing the lesson to its conclusion for the day.

“Next week, we will discuss a period that tested our strength even further – the outbreak of the Western African Conflict. We will break down how the tensions and hardships from the water crisis set the stage for a conflict that reshaped our region.”

“We will learn about the rise of General Malrik, a leader whose actions would ignite a war that brought both devastation and, eventually, a chance for rebirth and change.”

Gazing out at his students, their young faces bright with curiosity. Mr. Ekene dismissed the class with a parting message: “Remember, history is not just about the past; it is a lens through which we understand our present and work to shape our future.”